Unconscious Prejudices from my white past

I grew up in a white suburb of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in the 1960s. In our four year public high school of more than two thousands kids I don’t remember a single black face. Still, it was the 60s. We read “To Kill a Mockingbird”. We deplored the violent, ugly racism of the South that was often on display on the evening news. We examined ourselves for something we called “prejudice”. In schools and in churches we declared that we would strive to be “colorblind” in our encounters with people of other skin colors—an aspiration we now hear voiced by people who insist that aspiring to “colorblindness” is sufficient on its own. We were good kids. We thought well of ourselves—and, by and large, for the times, probably we were.

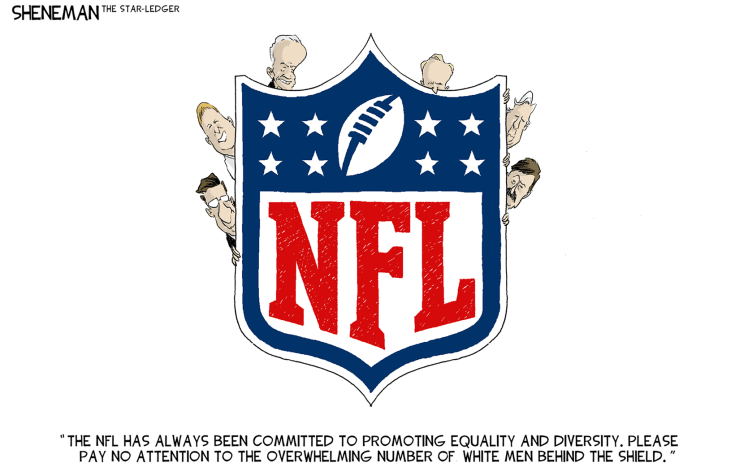

On Monday, February 7, Doug Muder in his “Weekly Sift” email published a post entitled “Racism in the NFL”. His article slapped me in the face with a realization about the social milieu in which I was so steeped as a teenager that I was blind to it. On the one hand, back then I was intellectually certain that skin color bore no genetic relationship to any sort of aptitude, i.e. beneath the skin surface there was what we called “equality”. On the other hand, in reading Muder’s article I recognized, painfully, that I had heard, and unconsciously absorbed—and never once thought to challenge—assertions about sports prowess, quarterbacking, and coaching, assertions that were based on race that were the diametric opposite of what the other part of my brain professed to firmly believe. Muder’s article awakened me to the systemically racist, but smugly “colorblind” social environment in which I was steeped and from which I passively absorbed.

Many on the right wing, especially those with white supremacist leanings, want us to look back at the racial progress of the 1960s as more than sufficient—we dealt with that, we’re all colorblind now, it’s all fixed, nothing to see here, let’s move on. Closer, honest examination of our country’s past and our own socially-molded attitudes is an unwelcome and threatening exercise when such consideration might shake the foundations of one’s own deeply held beliefs. Consciously or unconsciously, the backlash to the call to better understand ourselves gathers support from among these people for laws threatening, silencing, and muzzling the teaching of our history and literature in the public schools.

Electrons are cheap, so, for your convenience, I have pasted Muder’s article “Racism in the NFL” below. It is also free to read at his blog site, the “Weekly Sift”. I encourage you to sign up for his Monday emails. His view of the world is refreshing.

Keep to the high ground,

Jerry

Racism in the NFL

by Doug Muder

The lack of coaching opportunities for Blacks in the NFL is more than just the usual it’s-hard-to-break-into-management problem, and a new lawsuit explores why.

As far back as 1908, when Jack Johnson won the heavyweight boxing championship, sports have been a prime setting for America to work out its racial issues. Blacks might have been barred from most opportunities to excel, and what they managed to accomplish in spite of racial barriers could usually be minimized. But sporting events have objective outcomes. In the 1930s, for example, Whites who wanted to downplay Black achievements could claim that jazz wasn’t really music. But they couldn’t claim that Jesse Owens wasn’t really fast.

In sports, the 20th century was a long story of racial barriers falling and Black athletes succeeding. In 1947, Jackie Robinson was the only Black player in the major leagues. But he became the rookie of the year that season, and by 1949 he was the National League’s most valuable player. Willie Mays entered the league in 1951, and Hank Aaron in 1954. By 1981, the major leagues were 18.7% Black, but then percentages began to fall, possibly because Black athletes drifted into other sports. In 2016, major league baseball players were 63.7% White, 27.4% Hispanic, 6.7% Black, and 2.1% Asian.

Basketball is the sport most dominated by Black players: In 2020, about 3/4 of NBA players were Black, a number that has been relatively stable for some while. The change from majority White to majority Black happened fairly quickly: The first three Black players entered the league in 1950. By 1957, Bill Russell was the most important player in a Celtic dynasty that would win 11 championships in the next 13 years. Whether White owners and executives continued to have racist beliefs or not, there was no arguing with that kind of success.

The story of race in the National Football League has always been more complicated. The NFL had a handful of Black players when it was getting started in the 1920s, but instituted an informal color barrier from 1933 to 1946. That barrier was broken not through the efforts a crusading White general manager like baseball’s Branch Rickey, but out of legal necessity: When the Cleveland Rams moved to Los Angeles in 1946, they played in the publicly-owned Los Angeles Coliseum. Public accommodations couldn’t be segregated even in that era, so the Rams needed at least one Black player. The Washington Redskins became the last team to integrate in 1962, when the Kennedy administration similarly threatened not to let them play in a stadium on federally-controlled land.

The quarterback mystique. But even as Black athletes in many sports succeeded in blowing up the myth of White superiority, racism established a fallback position: Some Blacks might possess a raw animal physicality, but only Whites had the intellectual and moral virtues that made athletes truly admirable.

And so an article about base-stealing baseball players might emphasize a Black player’s blazing speed, but a White player’s painstaking analysis of pitchers and their moves. Black basketball players might be imposing Goliaths like Wilt Chamberlain, but (as the sports magazines of my youth told the story) White players compensated through smarts, hard work, and an indomitable will to succeed. That racial distinction was rarely spelled in so many words, but whenever I heard an athlete described as “crafty” or “scrappy”, I could be pretty sure he was White.

Baseball and basketball are inherently egalitarian sports — everybody bats, anybody can shoot — so this pro-White image-making had limited effects. But football is more corporate and specialized. In particular, a racial mystique developed around the quarterback position: Of course arm strength and other physical gifts mattered, but intangible (White) qualities like leadership and courage were more important, and quarterbacks needed the (White) mental capacity to analyze defenses and make sound decisions under pressure.

As a result, it took decades for football’s conventional wisdom to recognize that Black athletes could be good quarterbacks. The prophecy was self-fulfilling: High school and college coaches didn’t want to “waste their time” training unsuitable Black players to be quarterbacks, so by the time the quarterback pipeline reached the NFL, it contained mostly White players. As that pipeline combined with NFL coaches’ own racial preconceptions, Black NFL quarterbacks remained exceptional and usually had short careers until Warren Moon and Randall Cunningham became stars in the 1980s.

Naturally, if Black athletes lacked the cerebral and moral virtues needed to be good quarterbacks, it followed that they couldn’t be good coaches either. All sports have had racial barriers to management positions, as the larger society still does in many fields. (Bill Russell once explained the dominance of Black players in the NBA by semi-seriously observing that young Black men weren’t distracted by their opportunities in banking.) But no other sport has such a wide gap between its majority of Black players and its tiny number of Black coaches: 69% of players are Black, but only one of the 32 head coaches (Mike Tomlin of the Pittsburgh Steelers). With only a slightly higher percentage of Black players, the NBA has seven Black head coaches.

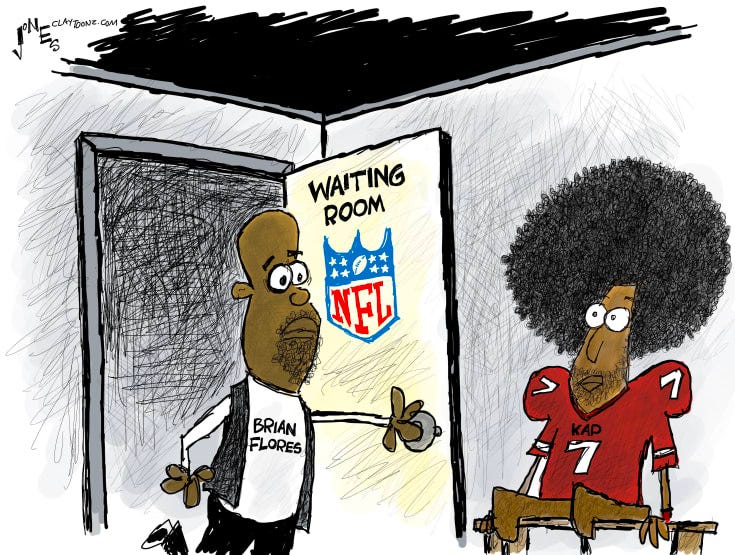

Until a few weeks ago, Brian Flores of the Miami Dolphins had been a second Black head coach. But he was fired at the end of the season, a move that seemed mysterious: In 2019, Flores had joined a team mired in mediocrity. The Dolphins had managed only one winning season out of the previous ten. His first season had been even worse: 5-11. But then he turned the team around, going 10-6 in 2020 and 9-8 in 2021. 2021 had seemed like two different seasons: The team had started 1-7 (and if Flores had been fired then, it would made some sense), but then finished 8-1. Teams that finish with that kind of spurt usually have high hopes for the next season. They don’t usually fire the head coach. So Miami’s Channel 4 seemed a bit puzzled:

During a Monday morning news conference, the primary issues [team owner Stephen] Ross cited for the decision to fire Flores seemed to have little to do with the on-field product and more with communication within the team’s braintrust — though there were no specific examples offered of how the team determined Flores wasn’t the right fit in those regards.

Anyway, life in the NFL. Flores moved on to apply for other coaching vacancies. And then, for a minute, it seemed like he had found something. The Patriots’ Bill Belichick — Flores had been his defensive coordinator during the Super Bowl winning 2018 season — sent Flores a text congratulating him on landing the New York Giants head coaching job.

The weird thing was, Flores hadn’t heard anything and hadn’t even interviewed for the job yet. That was supposed to happen in a few days. After a quick back-and-forth it turned out that Belichick had gotten the wrong Brian: The Giants had decided to hire Brian Daboll, a White coach who had also been a Belichick assistant at one point.

But even though they were telling people like Belichick that the decision was made, the Giants didn’t inform Flores. They went ahead with his interview, then announced that Daboll was their new coach.

Why they would do that has a simple answer: the Rooney Rule.

Rooney Rule. Named after former Pittsburgh Steeler owner Dan Rooney, the Rooney Rule says that NFL teams have to interview non-White candidates for coaching and management jobs. It puts no quota on hiring, but Black candidates at least have to get in the door.

It was established in 2003 after a similar controversy: Tampa Bay had just fired coach Tony Dungy (who would later win a Super Bowl in Indianapolis), and Minnesota had sacked Dennis Green (after his first losing season in ten years). A study showed that Black NFL coaches had, on average, better records than White coaches, but were less likely to be hired and more likely to be fired.

Clearly, the rule didn’t solve the problem. Nearly 20 years later, the NFL is down to one Black coach again. Instead, the rule has become a box-checking exercise, in which Black coaching candidates are put through charade interviews without being seriously considered.

They have long suspected this, but the Belichick text was the first time it could be established in a particular case.

The Flores lawsuit. Tuesday, Flores filed a lawsuit in federal court in New York (where the NFL is headquartered). It’s a class-action suit on behalf of

All Black Head Coach, Offensive and Defensive Coordinators and Quarterbacks Coaches, as well as General Managers, and Black candidates for those positions during the applicable statute of limitations period

The suit asks the court to declare the league in violation of several non-discrimination laws, to award monetary damages (both compensatory and punitive), and for

injunctive relief necessary to cure Defendants’ discriminatory policies and practices

And that’s where it gets interesting. What would a court have to do to “cure” the NFL of racism?

The problem is that each team hires only one head coach at a time, and those decision depend on subjective judgements: How well does this coach’s management style fit the team’s vision and the talent on the field?

So far this year, five of the nine coaching vacancies have been filled (all by White coaches), but it’s hard to pick out any one of them as a racist decision. The Jaguars, for example, just hired Doug Pederson, who in his last job won the Super Bowl with a back-up quarterback.

The fact that a coin comes up heads once doesn’t prove it’s rigged. But if it keeps coming up heads again and again, it probably is.

What Flores claims. Several of the specific charges in Flores’ lawsuit have gotten attention from the media, but not enough attention has been paid to the suit’s larger narrative.

For example, the accusation that Dolphins’ owner Ross offered Flores a bonus for losing games so that the team could get a better draft pick (an officially denied practice known as “tanking”), has been widely reported. But the larger implication is that hiring Flores in the first place was a sham: He wasn’t hired to succeed; he was hired to be the fall guy for losing seasons that would build a team that some other coach (presumably White) could lead to victory in the future.

Another former Black coach (Hue Jackson of the Cleveland Browns) has told a confusing story that supports Flores up to a point: At first he seemed to imply that he also was offered money to tank, but later backed off to claim only that the management above him was trying to lose.

I told [the Browns’ owner] that what he was doing was very destructive, to not do this because it’s going to hurt my career and every other coach that worked with me and every player on the team. And I told him that it would hurt every Black coach that would follow me. And I have the documents to prove this.

The Miami tanking scheme (which Flores obviously did not implement), also throws a different light on the official explanation of poor “communication within the team’s braintrust” as a reason to get rid of him.

In other words, the NFL’s problem is even bigger than the numbers suggest: Of the few Black coaches hired, how many were hired to take the blame for an intentional failure?

Prospects. The Federalist Society, which wouldn’t be able to find racism in a Confederate plantation, outlines the difficulties Flores’ suit will run into in the hardball world of anti-discrimination law.

What the lawsuit doesn’t contain, however, is actual proof that the NFL is a systemically racist organization and needs to be punished for discriminatory behavior.

Most of Flores’ allegations don’t come close to proving legally actionable systemic discrimination, which must involve finding racist intent or internal statistical “patterns” of inequity. He points out that the NFL currently employs only one black head coach (and three minority head coaches, counting Ron Rivera and Robert Saleh) in Mike Tomlin of the Pittsburgh Steelers. But judging an organization by one year of results is not actionable.

I agree with their analysis this far: Flores can’t win purely on the evidence that he cites in his complaint. But the class-action lawsuit is an open invitation for other Black coaches and coaching candidate to join his class. Hue Jackson is telling his story. How many others will chime in?

Informally, there’s a lot of sympathy with Flores. I’ve heard ESPN analysts quote unnamed Black coaches saying “I’ve been on that interview” where Rooney-rule boxes are checked without any real chance at a job. But does that mean they’ll come forward?

At some point, it’s not just about the law. The NFL needs public support. The racist blackballing of Colin Kaepernick is already a stain on the league, and so is the race-norming in the original concussion settlement. (Until a new settlement in June, Black players had a harder time claiming cognitive impairment, because the assumed baseline for cognitive function was lower for Blacks. In laymen’s terms: The league assumed Black players had less brainpower to lose.) Independent of what a judge might say, the NFL just can’t have a parade of Black players and coaches testifying about its racism.

And finally, there’s the discovery process. If Flores can get a look at NFL teams’ internal communications, who knows what he’ll find? The NFL is run by billionaires, and billionaires often assume the rules don’t apply to them.