We are in need of financial literacy

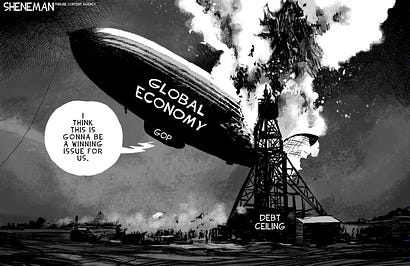

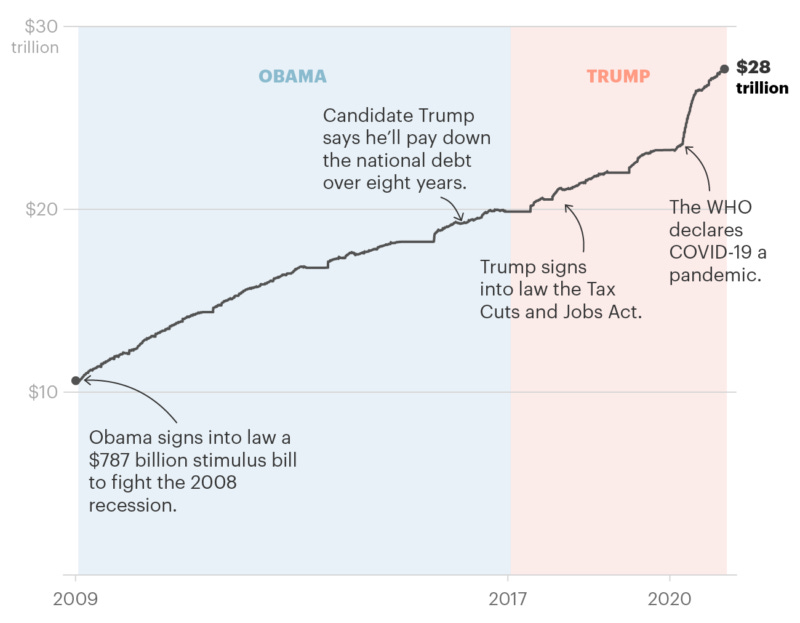

In the last months we have read a lot about the “debt ceiling”, the national debt, and the Republican threat to crash the national and global economy unless their wish list of spending cuts are granted to them. Never mind that the very Republican “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017” granting substantial (and un-expiring) tax cuts to corporations—thereby reducing revenue—was a significant contributor to the national debt of which they are now complaining. (Remember Rep. McMorris Rodgers’ drumbeat “Money in your pocket” as she promoted pretended that corporate tax cuts weren’t the real purpose of the Act?

The national debt is an incomprehensibly large number, nearly 32 trillion dollars. The Weekly Sift post by Doug Muder that I have copied below is the best examination of the meaning of the national debt and how it relates to the debt ceiling that I have read.

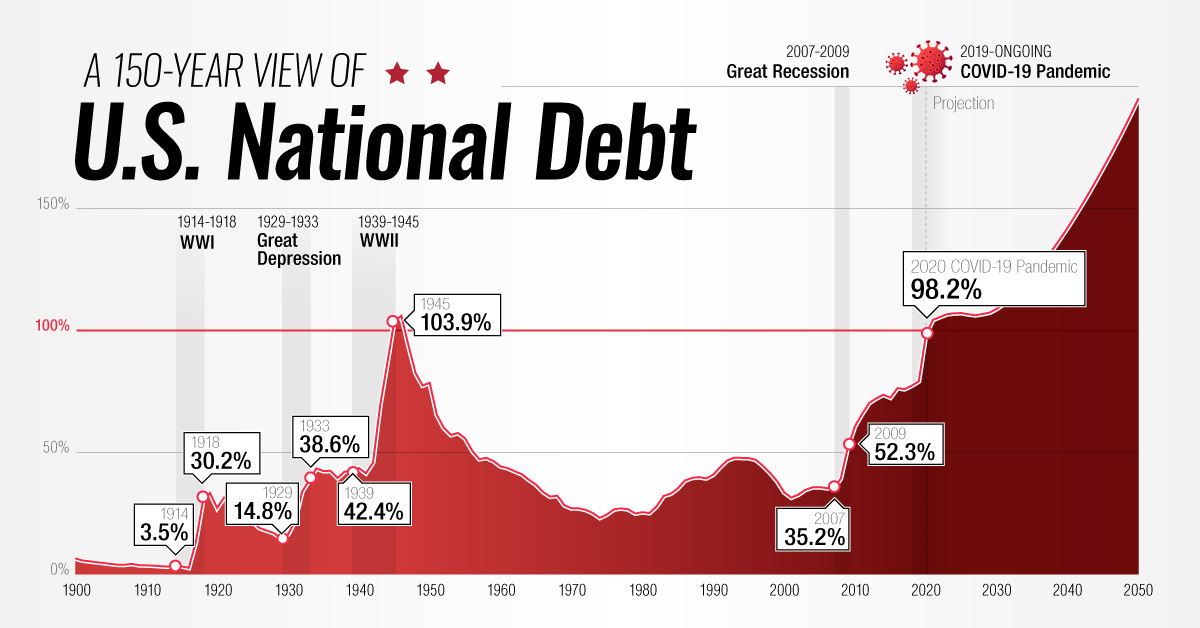

NOTE: 1) The first graph in Muder’s article, the “150 year view of the National Debt”, graphs the national debt as a percentage of the United States’ “GDP”, the “gross domestic product”, i.e. the sum total of good and services produced and consumed in a given year. This is better than expressing the national debt as a raw number of dollars in part because the buying power of a dollar changes over time (by about a factor of 10 in the last sixty years) and because the country’s ability to make good on its debt is directly related to the strength and size of its economy. 2) In that same graph the rise at the end that takes the percentage about 100% is a projection, not necessarily reality. (Note where the year 2020 is on the graph.)

Keep in mind that the national debt number is the long term sum of annual budget deficits and surpluses. The national debt represents the sum of money the government has borrowed over time. Just like in your personal finances, in any given year whether the government runs a deficit or a surplus depends both on the level of spending and on revenues. Republicans, having paid off their corporate supporters with over forty years of corporate and estate tax cuts, really, really don’t want to talk increasing revenues—only about cutting spending.

Once again I strongly recommend signing up for the Weekly Sift email (look for the sign-up in the left hand column of this page). I look forward to Muder’s writing every Monday.

After reading Muder’s piece for orientation, check out the quote appended below Muder’s article taken from a recent email from Rep. McMorris Rodgers (R-eastern WA) sent to selected supporters. Savor the inanity, particularly on account of its placement in a section of the email headed “Setting the Record Straight”.

Keep to the high ground,

Jerry

Does the US have a spending problem?

Doug Muder, The Weekly Sift, May 8, 2023

Compared to other countries, no. But if you think the US should be “exceptional” and that climate change is a hoax, maybe.

As House Republicans get closer and closer to forcing a debt-ceiling crisis that could result in the United States defaulting on commitments it has already written into law, American citizens need to raise their understanding of how all this works. Previously, I’ve written two posts on this theme: The first explained what the debt ceiling is and why we shouldn’t have one at all. (Only the US and Denmark have debt ceilings, and Denmark doesn’t play chicken with theirs. No other country inflicts these kinds of fiscal crises on itself.) The second looked at the history of the US national debt and how it accumulated.

Now it’s time to address the main argument House Republicans are making to justify playing chicken with an economic catastrophe: Sure, the US defaulting on its commitments would be bad, but it’s worse to do nothing, because our ever-increasing spending and debt is pushing us towards an even greater catastrophe.

In other words, a self-inflicted debt-ceiling crisis is the lesser evil. Steve Moore, the Club for Growth founder that Trump tried to appoint to the Federal Reserve Board, puts it like this:

The nation’s good credit standing in the global capital markets isn’t imperiled by not passing a debt ceiling. The much-bigger danger is that Congress does extend the debt ceiling, but without any reforms in the way Congress grossly overspends.

The first part of that claim is obvious nonsense: Not passing a debt ceiling certainly does imperil the US standing in credit markets. But let’s examine the second claim: Not just that the government spends more money than some people would like, but that doing so is pushing us towards a national catastrophe.

Spending. It’s a matter of simple fact that government spending and debt have gone up considerably — both in absolute terms and as a percentage of our annual GDP — in the late Trump years and since Biden took office. Basically, the Covid pandemic both cut revenue and required enormous government spending to avoid great public suffering while the private sector was largely shut down. The necessity of that deficit spending was a bipartisan conclusion; it happened under both Trump and Biden and was supported in Congress by members of both parties.

(Notice that the extreme right of the graph above is a projection to 2050, not something that has already happened.)

That increase in the debt built on a previous run-up during the Great Recession that started in 2007. Again, the stimulus spending and tax-cutting was bipartisan; it began under Bush and continued under Obama.

But looking forward, the US faces challenges that the two parties see differently. Democrats want the government to spend money on them, while Republicans don’t.

- Democrats see climate change as a problem that requires a major restructuring of the economy, moving away from fossil fuels and towards energy from sustainable sources. However, climate change is a classic externality — a real cost that falls neither on the producer nor the consumer of fossil fuels — so the market will not make this shift without government intervention. Republicans deny that climate change is a problem.

- Democrats want to shift healthcare — nearly 1/7th of the economy — from the private sector to the public sector. Medicare began this shift in the 1960s. ObamaCare continued it, and progressives like Bernie Sanders would like to complete it. Republicans would like to stop this shift, if not roll it back.

Abstract debates about “spending” are really about these two issues, plus the perennial question of how good a safety net the US should provide for its poor: Is it enough to keep people from starving in the streets, or should the government guarantee every American a decent life, whether they can find a job or not?

It’s worth noting that the other big government expenditure — defense — is largely bipartisan. In general, progressive Democrats would like to spend less on defense and MAGA Republicans more, but neither party has a consensus for major changes in our military posture in the world.

The politics of spending. The bill House Republicans recently passed reflected these priorities: It agreed to raise the debt ceiling for about a year (at which point we’d go through the same ordeal again), in exchange for

- capping “discretionary spending” — basically everything but Social Security and Medicare — at FY 2022 levels and letting them increase by only 1% per year.

- rolling back provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act to subsidize sustainable energy, while increasing production of fossil fuels

plus a few other things. The discretionary spending cap isn’t across-the-board, but also doesn’t specify the cuts. This allows Republicans to dodge when Democrats say they’ve voted to cut some popular program like veterans’ benefits. And of course, every program that gets exempted from the cuts means that deeper cuts will be needed elsewhere.

The White House has been attacking Republicans for proposing cuts to veterans’ care. Republicans in House leadership have responded that no cuts are intended. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy has promised he will protect the military from reductions, though the bill as written does not exclude them. And Kay Granger, the chairwoman of the House Appropriations Committee, has said border security remains a top priority.

This is a feature of our politics that I’ve noted before: The American people don’t really understand where government spending goes, so they support spending cuts in the abstract, while rejecting any specific list of significant cuts.

The two parties maneuver around that phenomenon: Republicans support vague spending “caps” that don’t specifically cut anything in particular, while Democrats try to pin them down. Do they want to cut defense? Veterans benefits? Health care? Education? No, of course not. They just want to cut “spending”.

Is government spending a problem? For Republicans, this is an article of faith, but it’s really not obvious. For example, look at Wikipedia’s list of countries by government spending as a percentage of GDP. (The US total accounts not just for federal spending, but state and local as well.)

As of 2022, the US was not an outlier in either direction, spending about 38% of GDP via government. That’s less that most comparable countries: the UK (45%), Germany (50%), Canada (41%), and France (58%) for example. But it’s also more than Switzerland (34%) and Israel (37%), and almost exactly the same as Australia.

And while government spending has been generally rising over the decades — it was less than 20% of GDP a century ago — the increase doesn’t look precipitous or out of control.

In short, if you argue that the US has a spending problem, what you’re implicitly saying is that we shouldn’t be like other nations. If you regard Germany or France as cautionary tales, then we need to cut spending before we wind up like them. On the other hand, if you envy countries like Denmark (49%), the Netherlands (45%), and Finland (54%) — Finland regularly comes out on top of polls about public happiness — then you can only shake your head at this “out-of-control spending” talk.

The ledger has two sides. So while the “spending problem” is debatable, it is obvious that the national debt is growing. Intuitively this seems bad (though I’ll push discussing how bad it really is off to a later post). But jumping immediately from a debt problem to a spending problem is sleight-of-hand. Spending 38% of GDP (or 50% or even more) through the public sector doesn’t necessarily create debt if we’re willing to pay taxes at that level.

Our debt problem (from the same Wikipedia list) comes from the fact that we’re only paying 33% of GDP in taxes. This is not high by comparison with other countries. South Korea pays 27% and Ireland 23%, but just about every other country we might compare ourselves to pays more: Germany 47%, Canada 41%, the United Kingdom 39%, and so on.

So it’s disingenuous to frame the debt as a national crisis, but take taxes off the table. In particular, the Trump tax cuts went mainly to corporations and the very rich, while adding trillions to the debt over a ten-year period. Most spending cuts are unpopular in themselves, but they’re particularly unpopular when you pair them with tax cuts, as in “We have to kick your cousin off Medicaid so that billionaires can keep the tax cuts Trump gave them.”

The private sector isn’t magic. Much of the debate about government spending is really about whether some necessary expense winds up in the public or private sector. We could, for example, cut government spending overnight just by closing all the public schools. Kids would still need to be educated, and most middle-class-and-above families would find some way to send their own kids to private schools (maybe with help from grandparents). Taxes could go down, but private expenses would go up.

Ditto for Social Security. We could end it an save everybody taxes. But you’d also have to worry about whether your parents or grandparents were starving, and maybe they’d have to move in with you.

All our highways could be toll roads run by private corporations. Taxes could go down, but you’d have to pay tolls.

The point I’m making here is that nothing magic happens when we move an expenditure from the public to the private sector or vice versa. Somebody still has to teach the kids, take care of the sick, and pave the highways. You don’t necessarily save anything just by paying those people out of a different piggy bank.

That observation is going to be important the next time we consider expanding national health care. Conservatives are going to freak out about the massive increase in government spending. “OMG! We can’t afford this!” But if the net effect is that taxes replace health-insurance premiums, we can. That’s the main reason government spending (and taxation) is higher in places like France and Germany: They’re buying stuff through the public sector that we buy through the private sector. People still wind up paying doctors and nurses to take care of them, but the money traverses a different route.

Spending and democracy. Finally, we need to recognize that the current situation results largely from what the American people want: The particular programs the government spends money are popular, while taxes are unpopular. The current spending and taxing levels were passed by the Congress the people elected.

The point of using the debt ceiling as a hostage-taking tactic is to circumvent democracy. Yes, the people did narrowly elect a House Republican majority in 2022, but Republican candidates ran on issues that have largely vanished from the House Republican agenda, like crime. They certainly did not run on a list of spending cuts, and in fact they still have not produced such a list, because they know it would be unpopular.

The American people have also elected a Democratic Senate majority and a Democratic President. (Both of those happened in spite of structural factors that allow Republicans to win without representing a majority of voters, like the small-state bias in the Senate and the Electoral College.) The Republican House should not get to control the agenda simply because they are apparently willing to push the economy’s self-destruct button unless they get their way.

So what should happen? The debt ceiling should play no role, and Congress should work out a budget for next year, adjusting both the taxing and spending sides of the ledger. Republicans should have a bigger say in the next budget than the last one, because they won the House majority. But both parties should publish their budget priorities and see how the American people like them.

So is there a spending problem? Not really. Not by international standards and not compared to what the people want. What the government spends money on may or may not be what you want it to spend money on. But that’s why we have elections.

McMorris Rodgers’ “Weekly Newsletter” email dated May 12:

Contrast Doug Muder’s explanation above to this McMorris Rodgers’ gem of political and economic nonsense.

A number of people have reached out this week concerned about a bill I helped pass last month called the Limit, Save, Grow Act [the Republican list of ransom demands] that would responsibly raise the debt ceiling. Unfortunately, there has been a lot of misinformation flying around about what this bill does, so I think it’s time to set the record straight. [Really???]

Despite what President Biden and the Democrats want you to believe, this legislation does NOT cut veterans benefits, Social Security, or Medicare. All it does is set a topline budget number – it does not outline any cuts to federal programs, and it does not replace the annual federal funding process. [i.e. they want to slash spending but they don’t want to specify what programs they plan to cut.]

I understand the urgency of the situation surrounding the debt limit, which is why I helped pass this legislation to ensure America doesn’t default on our debt and fight inflation to lower costs for the hardworking people of this country. [That is an internally nonsensical statement. Making sure no debt default occurs requires the simple act of raising the debt ceiling, not proposing undefined cuts in spending.] But in order for our divided government to work, Democrats need to come to the table. My hope is that my colleagues across the aisle will work with us sooner rather than later to deliver a solution for the American people. [The actual solution is, of course, to raise the debt limit, not to play chicken with the economy.]