The forces that feed homelessness

Over the holidays I watched “Leave the World Behind” on Netflix. It was both entertaining—and disturbing—well worth the time to watch. The story begins with the wife of a family of four, played by Julia Roberts, arranging an online rental of a house “near the beach” for a weekend getaway. Amanda (Roberts) is an advertising consultant. Dad is a sociology professor. They have two teenager children. They live in a spacious brownstone apartment in New York City. The weekend rental is a very modern, three story house on several wooded acres hinted to be on Long Island, but with an implausible, over-the-water view of a skyscraper skyline. The price tag for the two night, weekend rental (based on later conversation) is at least a couple thousand dollars, which seems to faze no one. Later in the movie, the dad character, played by Ethan Hawke, on at least two occasions (rather implausibly for any college professor I’ve ever known) pulls out his wallet and peels off hundred dollar bills, noting that his credit cards no longer work.

The rental is owned by a family of three, two of whom we meet later. The dad, played by Mahershala Ali, is well connected and cultured. He works in finance, like so many of the über-wealthy. (As a man of such wealth, why he feels the need to offer this house as a vacation rental is never made clear.) The Long Island rental is wildly open, spacious, and elegant. Each of the bedrooms is big enough to use as a dancehall—even with the beds still in place. One can only imagine the number of square feet per person are under the control of the people depicted in this movie—and that’s without considering that this Long Island rental is just the weekend abode of the owner’s three person family (their “home” is “in the city”).

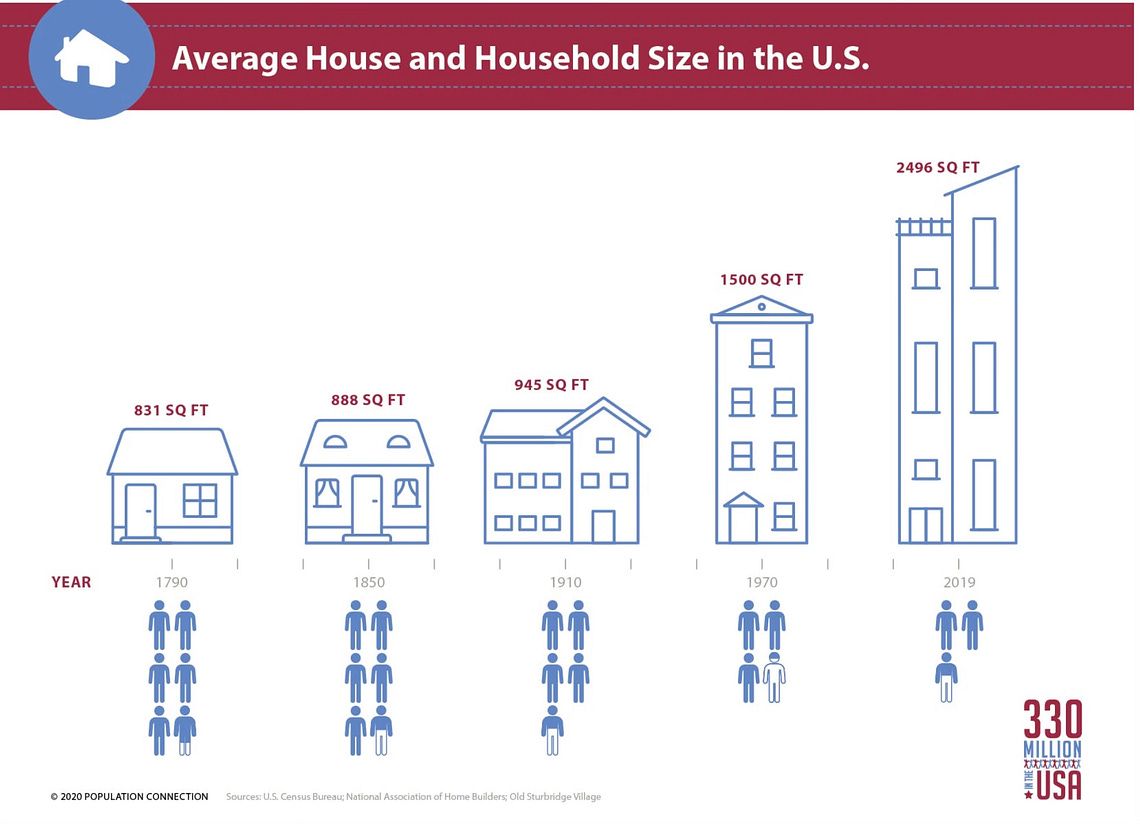

Obviously, “Leave the World Behind” is fiction—but it mirrors a housing reality that has crept up on us in real life: the average house in the U.S. has massively increased in size even as the average number of people occupying that average house has dwindled.

Even the conservative American Enterprise Institute (AEI) documents the near doubling of the average square feet per person in new single family homes in the last fifty years. AEI spins this doubling of average living space per person in newly constructed homes as a wondrously good thing—an example of the supposed triumph of free market capitalism.

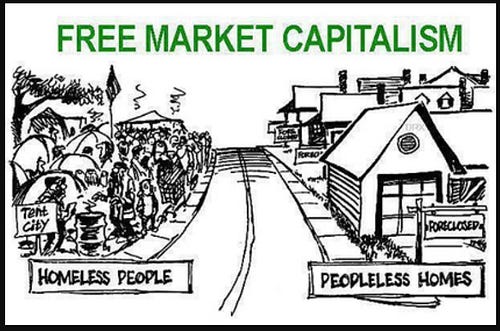

But mathematical averages mask a reality AEI would rather not acknowledge. This image comes to mind from a post by Robert Reich, former U.S. Secretary of Labor.

Over the last forty years of “free market” Republicanism (and “neoliberaleconomics”) it is no secret that changes in the rules that govern how the economy works have been shifted in a way that has sucked wealth upwards. Wages have stagnated while investments and investment income have burgeoned (think of the mostly steady rise of the stock market—as well as the bumpier rise in home prices over those forty years). The painfully obvious rise in visible homelessness is a symptom of this growing wage and wealth gap—a gap that won’t move toward solution until we address the economic rules changes that brought it about in the first place.

The majority of my readers probably belong to the aging Baby Boomer generation, as do I. Many of us (including me) benefitted from excellent, well-funded public schools, relatively affordable college tuition, government-backed low interest mortgage loan programs, and retirement programs that have helped us accumulate some tax-advantaged savings. We lived in a sweet spot in the economic system (at least for white Americans).

Consider how many square feet of living space you own and more or less exclusively occupy. (The “more or less” is meant to recognize occasional short term rentals, as in Airbnb.) Is it more than the per person average of around 1000 square feet (a square 32 feet on each side)? Now consider the square footage (whether you own one or not) in existing lake homes, massive and only periodically occupied ski homes, ranch getaways (think Ted Turner), and what would otherwise be long term rental square footage now tied up in Airbnbs and VRBOs. Consider that a lot of that square footage may be owned and managed (like an increasing number of long term rental units) by wealthy investment groups that only exist because there is a massive amount of money floating around at the top looking for ways to grow itself. All of the above listed square footage is totally out of reach of the average wage earner with no inherited wealth who struggles to come up with enough money to pay the rent and avoid economic eviction.

We all noticed the recent heated rise in Spokane’s home prices driven by people moving here with money from sales of homes in higher priced markets. Many home owners complained bitterly (and incorrectly) that since their assessed value had doubled their property taxes would be unaffordable. (Property taxes rose—but not proportional to the rise in assessed value.) What we may not have noticed is that home sales prices rarely drop (2008 is an exception). Instead, fewer homes come on the market as asking prices remain nearly steady. Who wants to sell, give up their square footage, and then be only afford to buy a smaller place with a similar monthly mortgage payment? (This is the conundrum posed by our ubiquitous fixed-rate thirty year mortgage, nearly a U.S. exclusive—but that’s a story for another day—and only one small piece of the puzzle.)

The rules by which the economic game is played have changed in the last forty years. Those changes are driving the wealth and wage disparity we see now that are fueling the relentless increase in homelessness nationwide, but especially in the nation’s most economically vibrant cities. Local governments can and should chip away at economic eviction with zoning changes and rent-rise regulations. They can mount efforts to provide supportive housing for those already rendered homeless, but local governments have little power to address the fundamental rules of the economic game that are fuel to supply of homeless people. Such changes will require state and federal level action—action that will be strongly resisted by Republicans armed with forty years of Republican rhetoric.

Keep to the high ground,

Jerry