Seeing Chevron Doctrine as a local issue

On Monday I posted PFAS, Forever Chemicals, and Our Water concerning the evolving story of “forever chemical” groundwater contamination on Spokane’s West Plains. Part of that story is Spokane County Commissioner French’s and Spokane International Airport CEO Larry Krauter’s quiet efforts 1) to push back against regulations surrounding PFAS, 2) to avoid revealing well test results, and 3) to block data gathering.

Later that day I read Doug Muder’s January 22nd post on the significance of long-running national Republican efforts to eviscerate the “administrative state” by challenging an arcane-sounding concept dubbed “Chevron Doctrine” in the U.S. Supreme Court case.

“Chevron Doctrine” seems arcane, far away, and of little personal concern, but comes into focus when applied to rules meant to protect our health from environmental contamination close to home. U.S. Representative Cathy McMorris Rodgers’ endless blather about “reining in regulation” and “unleashing the free market” came into stark focus with Muder’s words, “In a complex modern economy, there are countless ways for corporations to make money by killing people.”

Like me, many of my readers have lived most of our lives in a comfortable partial fiction: that, thanks to the ecology movement of the 1960s, the passage of the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act, and the establishment of the Environment Protection Agency, our government protects us from industry poisoning the air and water upon which our lives depend.

But let me turn you over the Doug Muder’s brilliant piece copied below. Keep the West Plains and PFAS in mind. (Muder’s The Weekly Sift should be on everyone’s Monday morning reading list.)

Keep to the high ground,

Jerry

Monkeywrenching the Regulations that Protect Our Lives

Doug Muder

Jan 22

The Supreme Court’s attempt to scuttle the Chevron Doctrine is part of a much larger program.

Over the last few weeks, Court-watchers have been trying to sound the alarm about the prospect of scuttling what had (until recently) been a fairly arcane bit of legal interpretation: the Chevron Doctrine. Lawyers understand how important it is (the Court has applied it in over 100 cases in the last 40 years), but it’s tough to get the general public to pay attention, much less to be up in arms about its possible demise. But there actually are good reasons to be up in arms.

A fairly standard thing to do at this point would be to tell you what the Chevron Doctrine is and where it comes from. I’ll eventually get around to doing that — click the link if you really can’t wait — but I’d rather have you keep reading for a few more paragraphs before you bookmark this page with the idea of getting back to it when you have more time.

Blood money. So instead I’ll back up a few levels and start with the underlying problem: In a complex modern economy, there are countless ways for corporations to make money by killing people. They can kill their customers by selling products that will crash them into trucks or suck them out of airliners or cause heart attacks or give customers cancer or salmonella or some other disease. They can kill their employees with unsafe workplaces. They can kill their neighbors by pumping poisons into the air or water. As AI catches on, products may start killing people and we won’t even know why.

Sometimes corporations very consciously make the money-for-lives tradeoff, as the tobacco companies did for decades, and as the gun manufacturers are still doing. But sometimes they just don’t know, at least at first. They have a product, they make money off of it, customers seem happy with it, so why look any deeper than that? Diacetyl makes microwave popcorn taste more buttery — what’s not to like?

As individuals, we’re more or less helpless to protect ourselves. No one has the time or the expertise to analyze every single thing they use or come into contact with. That’s why we rely on government regulation, agencies like the FDA, EPA, FSIS, and others, to protect our lives. (Other agencies, like the SEC and the FDIC, protect our money from the kinds of scams that were endemic prior to the New Deal.)

Government regulators get their power from two sources: Congress and the President. Congress creates the agencies, defines their missions, and funds them each year. Meanwhile, the President appoints the people who set the policies to accomplish those missions. Ultimately, Congress and the President get their power from the voters.

But here’s the problem: The marketplace moves much faster than our political system. New products, new drugs, new food additives, new pollutants, and so forth appear every week. Imagine the dystopia we’d be living in if Congress, which strains to pass basic legislation to keep the government’s doors open, had to pass a new law to regulate each one.

Well, you may not have to imagine much longer, because the Supreme Court’s conservative majority seems hellbent on taking us there.

Delegated power. The way the regulatory system currently works is that Congress passes a few foundational laws that give the agencies abstract goals, and then lets the agencies hire experts who figure out how to pursue those goals.

A typical example is the Clean Air Act. The CAA was first passed in 1963 and then overhauled in 1970. It established air quality standards (NAAQS) for a few well-known pollutants like carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, and lead, but then it defined a general category of “hazardous air pollutants” (HAPs) made up of other gases and particulates that “threaten human health and welfare”. It tasked the EPA with making and maintaining a list of HAPs and creating emission regulations for controlling them.

Hold that in your mind for a minute: In passing the CAA, Congress banned or controlled substances that the members of Congress had never even heard of. That’s how the regulatory system works.

That’s a lot of delegated power, particularly power over corporations that don’t like being controlled. And yes, their wealth does give the companies opportunities to influence the system — say by bribing or otherwise inducing congresspeople to give them various exemptions, or by letting regulators know they can have cushy jobs after they leave government if they behave themselves — but it’s never enough.

What corporations would really like to do is monkey-wrench the regulatory system in general. And the best way to do that is to interrupt the flow of delegated power from Congress to the agencies: Make Congress pass a new law every time there’s some new thing to regulate. In a Congress where even saving lives can be a partisan issue, and where a bunch of small-state senators can lock things up with a filibuster, even the most obvious new regulations can be stalled indefinitely or watered down to nothing.

So the basic strategy for restoring corporations’ ability to profit by killing people has two pieces

- Logjam Congress.

- Prevent Congress from delegating its regulatory power to anybody else.

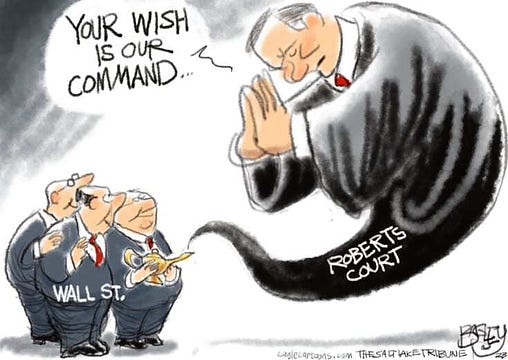

A three-pronged attack. With the second part of that plan in mind, corporate money begat the Federalist Society, and the Federalist Society (with the assistance of presidents who lost the popular vote and Senate “majorities” that don’t represent a majority of voters) begat the six conservative justices on the Supreme Court. Since gaining control of the Court, those justices have been working hard to fulfill the mission their corporate masters assigned them.

The most direct idea for keeping Congress from empowering regulatory agencies is known as the Nondelegation Principle: basically, that Congress can’t, as a matter of constitutional principle, delegate power that is inherently legislative. Some version of this idea is necessary, because otherwise Congress could authorize the president to be a dictator and then go home. But since 1928 delegation has been considered OK if Congress provided an “intelligible principle” for the agency to follow (like protecting human health and welfare from air pollutants).

But in a dissent in the Gundy case in 2019, Justice Gorsuch proposed a much stricter limit: Agencies can only “fill in the details” of laws, and can’t do something sweeping like, say, compile a list of dangerous pollutants to regulate. Fortunately, he didn’t get the majority to go along with him on that. But he’s still working on it, and the composition of the Court has changed since then. Expect to hear more about nondelegation sometime soon.

A second idea for reining in regulatory agencies is the Major Questions Doctrine, which the Court has created out of whole cloth over the last 25 years. Major Questions is a response to something that happens fairly often: Circumstances change in such a way that a provision in a law that seemed relatively minor at the time it was passed ends up granting an agency significant power. Major Questions allows the Court to say, “No, no, no. The law may say that, but Congress didn’t really mean it. If they’d intended to delegate such a large power, they’d have said so explicitly.”

So, for example, the Obama administration EPA decided that (due to the previously unforeseen problems of climate change), the Clean Air Act gave it the power to regulate carbon dioxide emissions from power plants. The Court nixed that in West Virginia v EPA. Carbon emissions, it said, are so central to the workings of our economy that (regardless of the text of the CAA) Congress would never have delegated that power without an explicit statement.

Now, there are four major objections to the Major Questions Doctrine:

- The Constitution never mentions it.

- The Court has never clearly defined what a “major question” is, so it has given itself permission to interfere (or not) whenever it feels like it.

- The law says what it says, even if Congress didn’t foresee all the possible applications.

- If Congress really didn’t intend to delegate that much power, it could pass a law to take power back. (But of course, that puts the logjam-Congress shoe on the other foot.)

One recent use of Major Questions was to torpedo OSHA’s rules about large employers vaccinating their workers against Covid. Yes, OSHA’s mission is to protect workers from unsafe working conditions, and yes, working next to an unvaccinated person during an epidemic is unsafe, but … Congress couldn’t really have intended that, could it?

One thing you’ll notice about Major Questions: It allows the Court to substitute its own judgment for both the plain reading of the law and for an agency’s interpretation of that law. And that brings us (finally) to the Chevron Doctrine.

Chevron. Back in the Reagan administration, all the ideological arrows pointed in the other direction: Reagan’s appointees were conservative, while judges tended to be liberal. In particular, the EPA was run by Justice Gorsuch’s mom, Anne Gorsuch.

Anne’s EPA had drastically limited its interpretation of what a “source” of pollution meant under the CAA. Previously, just about any change that introduced new pollution was considered a new source, and required EPA approval. But the new interpretation said that, say, an entire factory or power plant was the source of pollution, and could be substantially reconstructed without triggering EPA supervision.

The Natural Resources Defense Council sued to try to block something Chevron was building, but the Court ruled in Chevron’s favor by creating the Chevron Doctrine: When some part of a law is ambiguous, a court should defer to the interpretation of a regulating agency rather than impose its own interpretation of what Congress really meant. An agency couldn’t make up a ridiculous interpretation, but as long as its reading was plausible, the courts should yield to it. (An eye-glazingly detailed history of the Chevron case is in this interview between David Roberts and Dvid Doniger.)

But remember: the ideological arrows were pointing in the opposite direction from today, so Chevron was a conservative principle that was championed by conservative justices like Anton Scalia. The arguments he made were the same ones liberals are making today: Agencies have technical expertise that courts can’t compete with, and (because they ultimately get their power from Congress and the President), they’re closer to the voters than judges are. So Chevron is not just prudent, it’s democratic.

This kind of humility is sometimes called judicial restraint. For many many years, it was the hallmark of conservative jurisprudence: Activist liberal judges should restrain themselves, because they’re not as smart as they think they are, and because it’s undemocratic to remove issues from the political process.

But now conservatives have control of the courts, so humility is out the window. Apparently, judicial restraint was never actually a conservative principle, it was just a rhetorical device to keep liberal judges in check. Activist conservative judges, on the other hand, should have free rein to do whatever they want.

So Chevron has to go. The Court is using two fairly obscure cases (involving fees paid by the fishing industry to the National Marine Fisheries Service) to tee up an attack on Chevron. No one knows exactly what the ruling will say yet, but the questions the justices were posing during oral arguments point at a complete revision of Chevron that could make the Supreme Court also the Supreme Regulator; whether any given agency was interpreting its authorizing legislation properly would be for the Court to determine.

The practical implications of sinking Chevron could be enormous: Literally thousands of cases have been decided on that basis in the last 40 years, and any of them could come up for a rehearing. Plus, literally every regulation on the books will become a legal battleground, with the Supreme Court’s six conservative justices being the ultimate deciders.

In short, a committee made up of six foxes is about to take over the regulation of every chicken coop in the country.

ERRATA: In Monday’s post, PFAS, Forever Chemicals, and Our Water, I should have identified the author of RangeMedia.co’s article “Airport CEO: Lawmakers should ‘wait and see’ before banning toxic PFAS” as Aaron Hedges. Instead, I incorrectly named Erin Sellers. Both do great work.